Carlo Battain of Parker KV explains the many aspects of engineering that are involved in the quest for clean, efficient power generation

Carlo Battain of Parker KV explains the many aspects of engineering that are involved in the quest for clean, efficient power generation

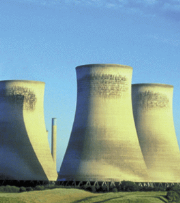

Power generation is the fundamental technology that keeps the modern world turning. As global demand for energy increases, so too does the demand for reliable capacity produced from both traditional hydrocarbon energy sources and new technologies such as renewables. And, just as important as new technologies is refining current technologies to make them easier to install, use and maintain.

All power generation systems are essentially the same – a turbine driving a generator. This article focuses mainly on gas turbines, although much of what is discussed could be applied to hydroelectric turbines, wind turbines and nuclear power.

It should also be noted here that size can vary greatly – it is natural to think of generating stations supplying power capacity to a large population, but smaller systems are to be found on industrial sites, in aircraft, on farms, country estates and other remote communities, as CHP (combined heat and power systems) for a block of flats or housing estate, and in hospitals.

The term ‘gas turbine’ is something of a misnomer, as they often run on liquid fuel. Increasingly they are dual fuel or multi-fuel, able to run with a number of different fuels. There is also a trend towards using biomass, ground source gas and waste gas fuels.

The term ‘gas turbine’ is something of a misnomer, as they often run on liquid fuel. Increasingly they are dual fuel or multi-fuel, able to run with a number of different fuels. There is also a trend towards using biomass, ground source gas and waste gas fuels.

This has led to an increased emphasis on the various aspects of fuel management. A fuel that is not 100% clean will inevitably cause residue build-up on the turbine blades and reduce efficiency, possibly leading to major damage.

Therefore, there is much focus on enhancing current gas purging technologies and enhancing fuel delivery control systems. There are parallel developments in water injection systems, which add water to the fuel mixture to increase power and reduce emissions, and misting or fogging systems which use water to cool the turbine. These in turn create a need for a drain valve system.

Valves and systems

The one thing that all of these systems have in common is valves, all of which work on similar principles and have similar engineering needs. Although in concept, valves are fairly simple, in reality they are far more complex as they need to offer guaranteed long reliable working lives.

To meet these needs, Parker KV has developed all-cartridge designs that are in complete stand alone sub-systems. The idea of this is that they are drop-in installation and fit and forget. They can be bespoke to a particular application or standardised for wide use.

Turbines have to have long operating lives, yet also need low maintenance requirements so that they can operate uninterrupted for extended periods. Typically a turbine will have a specified life of 12-15 years, but it is realistic to assume it will in fact give 20 or more years of service. The maintenance intervals will also be very low. It is not usual for a turbine builder to specify to the sub-system manufacturers a maintenance profile that says total reliability of operation for seven years, at which point an overhaul or upgrade will be scheduled with equally stringent requirements.

This actually makes it easy for valve package manufacturers. Such demanding requirements are only achieved though robust designs, precision manufacture, quality materials and accurate assembly. And with all these in place, performance can be ensured for far longer than seven years.

This actually makes it easy for valve package manufacturers. Such demanding requirements are only achieved though robust designs, precision manufacture, quality materials and accurate assembly. And with all these in place, performance can be ensured for far longer than seven years.

It is possible to argue that this is over engineering, but considering the cost and consequences of unscheduled down-time and breakages, it is a very small price to pay indeed.

Analysed over time, it is possible to see that the biggest trend in design is towards more and more modularisation. For instance, fuel systems were once assembled on-site, but now almost always come as a complete module, consisting of a manifold, valves, tubing, casing, injectors etc.

This trend started in the aerospace field three or four decades ago when the cost of aircraft manufacture had to be addressed to allow high volume, (relatively) low cost production so that the emerging demand for mass air travel could be addressed.

Technology transfers

The enabling technologies, such as modularised turbine sub-systems, have since transferred into other fields and are now enjoying a new resurgence as power generation technology develops for the new century. Relatively small turbines for local CHP, small scale and micro-generation, agricultural projects based on biomass and biogas etc, will only be viable if initial capital costs are contained. Standardised, modularised turbine systems are therefore critical to the development of these important green technologies.

These new installations will not be able to support maintenance hungry technologies, so once again low maintenance modular solutions will prevail.

These new installations will not be able to support maintenance hungry technologies, so once again low maintenance modular solutions will prevail.

Finally, it is worth considering the likely development routes of the new and emerging markets such as India, China, South America and Russia. Their need for power is set to rocket.

They will not be able to, nor want to, support the conventional technologies developed in the west over the last few decades. They will want high performance turbines, including ‘green’ solutions, but will not have the infrastructure to provide the levels of maintenance and management traditionally required. Therefore, the big projects that will provide the backbone of their national power systems will help redefine new levels of performance and reliability in power generation.

We see that the power generation markets have tremendous pressure to both develop new technologies and to refine existing ones to new levels of performance. The technology and concepts that have been around for 50-100 years are therefore still far short of plateauing out to a mature design, so turbine engineers are going to be at the cutting edge of design and development of at least three or four more decades to come.